Building Nothing Out of Something

The first verse of Modest Mouse's 1996 song "Whenever I Breathe Out, You Breathe In (Positive/Negative)" is the most evocative description of depression that I've ever heard:

I didn't go to work for a month

I didn't leave my bed for eight days straight

I haven't hung out with anyone

If I did, I'd have nothing to say

I didn't feel angry or depressed

I didn't feel anything at all

I didn't want to go to bed

And I didn't want to stay up late

My work attendance and bedridden stats, compared to 21-year-old Isaac Brock's, are rookie numbers. I've never been diagnosed with depression, nor have I ever felt inconsolable for days on end. Recently though, I have felt a renewed connection with these lyrics.

I haven't published anything in almost three months. I've only written three paid pieces this year. I wrote 33 editions of this newsletter in 2024; it's almost December 2025 and I'm just starting number 11. These days, I barely ever feel like writing anything.

Thankfully, my current version of "Whenever I Breathe Out, You Breathe In (Positive/Negative)"' only concerns one aspect of my life. I still find plenty of solace in my personal relationships, hobbies, and longtime side gig of bartending. But over the past couple of years, professional music writing has been slowly slipping away from me, and I didn't fully reckon with that until the few remaining dregs started swirling.

I've always known, at least in the back of my mind, that this was untenable as a career—that's why I've had a side gig since 2017. What kept me going was a shred of optimism that still flickered no matter how many shuttered publications, layoffs, or unanswered pitches piled up over the years. It saddens the hell out of me to report that my once-steady pilot light has all but gone out.

I fully understand why I no longer land pitches at a fraction of the rate I used to, and I hold no ill will towards anyone on the receiving end of those propositional emails. After all, I rarely respond to the PR emails that I get! The market has been consistently shrinking since I started college in 2009, and in addition to that, music criticism has always been something of a young person's game. What bums me out is the fact that I've become the guy in his mid-30s that I always swore I'd never be: someone whose curiosity and zeal for discovery and critical analysis has sharply waned. If it still made financial sense for me to spend hours listening to every new release and subsequently formulating publishable opinions, I doubt this would be the case, but it's been increasingly difficult for me to view that process as personal enjoyment rather than unpaid labor.

I started this newsletter just over two years ago in reaction to a media landscape that already seemed plenty hostile. I noticed that I was ignoring most of the promo emails in my inbox, so I sought to reinvigorate myself by featuring a weekly playlist culled from those submissions. It also seemed like an opportunity to generate a modest-but-independent stream of income, based on similar endeavors by other writers that I know. If you've paid attention to Inbox Infinity since its September 2023 launch, you've noticed that I haven't just published less frequently than initially planned, but that I've also entirely abandoned my mission of spotlighting submitted songs every week. As it turns out, the $400 that this newsletter has earned me annually hasn't been enough to motivate me to follow through.

I wanted to do it for the love of the game. I also wanted to be able to support myself in the field that I studied in college and have spent my entire adult life pursuing. But now I find myself almost completely devoid of the enthusiasm I once had for seeking out, listening to, and writing about new music. This defeatism has inevitably steered me towards the comfort of old favorites, and that's why I'm writing about Modest Mouse this week.

~~

My story with the band's 2000 compilation, Building Nothing Out of Something, reads as a classic Millennial meet-cute.

As a young teen in Washington in the mid-2000s, I was well acquainted with two Modest Mouse singles from their 2004 commercial breakout, Good News for People Who Love Bad News (for those curious, I've already shared my views on that album in this very newsletter), but at the time I had no idea that they'd been a band for a full decade prior.

Back then, my primary sources for music discovery were alternative rock radio, the random assortment of CDs at my local library, and perhaps most crucially, my friends' older brothers. Eldest children like myself have the privilege of shaping their younger siblings' taste, but the distinct disadvantage of lacking a built-in tastemaker living under the same roof. My friend Tom's brother Steve singlehandedly got me into hip hop by burning me a CD with A Tribe Called Quest's "Scenario" and Outkast's "B.O.B." on it; ditto for my friend Emerson's brother Otto with 2000s alt-rock rock like The Strokes, Bloc Party, and Arctic Monkeys. But of all the older brothers, one had an outsized impact on shaping me as a music fan.

When I met Anders in fifth grade, his brother Carsten was already in a band that opened for weird adult artists at our local all-ages venue. I first experienced live music seeing him and his friends play infectious, Weezer-inspired power-pop and then getting a ride home once, say, Elf Power or Mount Eerie scared me away (I did stay for a Thermals set on the The Body, the Blood, the Machine tour, and that was sick). (Another side note: the drummer in most of Carsten's bands was even younger than me, and now he has credits on albums by The War on Drugs, Craig Finn, Matt Berninger, and chart-toppers by Chappell Roan and Olivia Rodrigo.) Carsten's impeccable taste made its way onto his family's iMac, and so from a young age, I constantly demanded new mix CDs from Anders.

The CD in question opened with a few requests (I want to say "My Sharona" was on there?), but it also featured "staff picks" like the song "American Girls" by one-off Weezer side project Homie. The back half was strange, though. There were four consecutive songs that all sounded like the same band, which departed from the usual eclectic structure of a mix CD. When I asked Anders about it, he had no idea how these songs ended up on there, nor what band it was.

It wasn't until five or so years later that I realized that I knew the first four tracks from Building Nothing Out of Something like the back of my hand, despite only purposefully delving into Modest Mouse's back catalog once I hit college. If I had a more finely tuned ear at age 13, I might've clocked the voice from "Float On," but this earlier material is so different that I forgive my younger self for his lack of recognition.

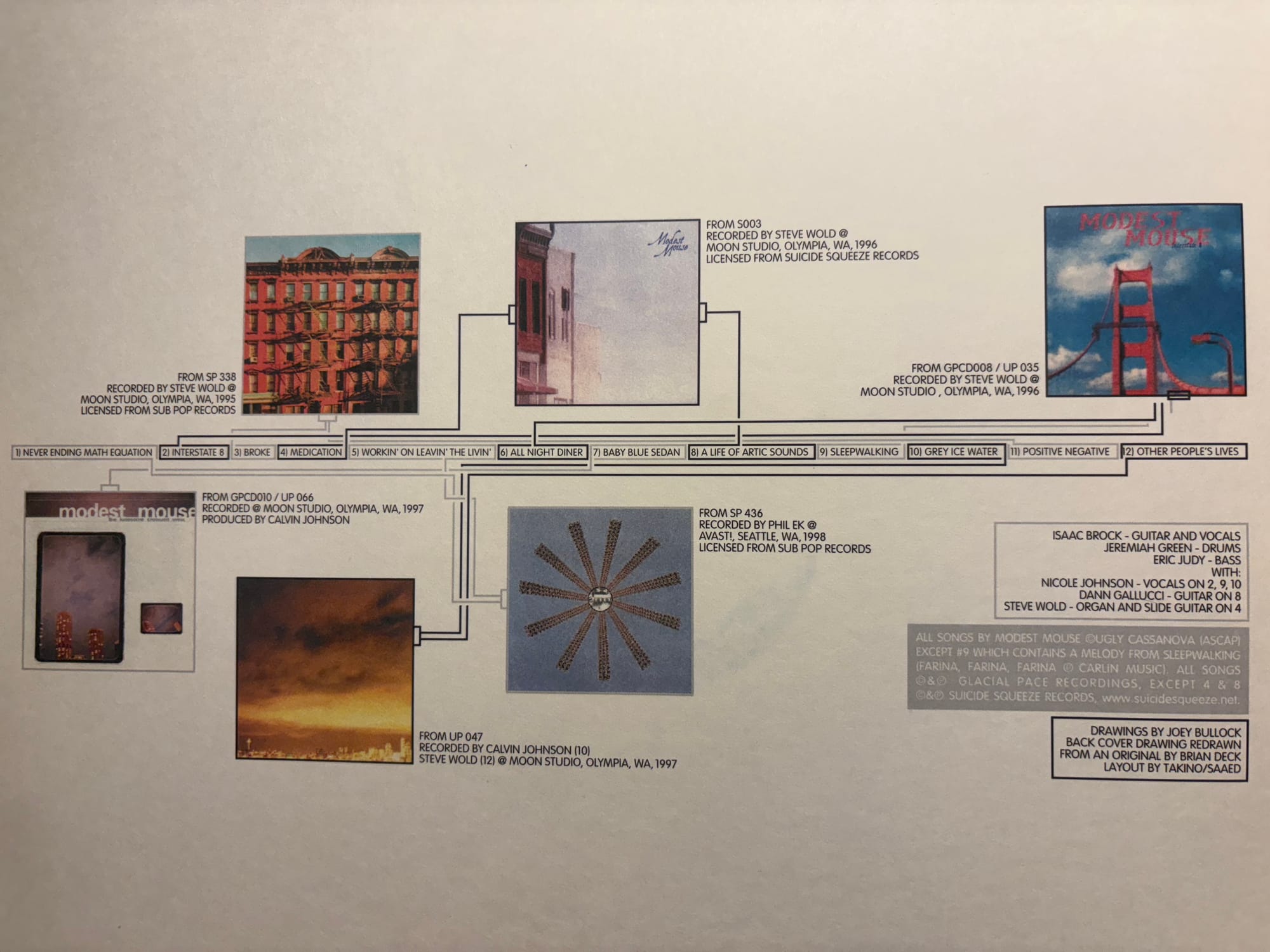

Modest Mouse released Building Nothing Out of Something between their two undisputed masterpieces, 1997's The Lonesome Crowded West and 2000's The Moon & Antarctica. Its 12 tracks had all been previously released, but none appeared on the band's first two albums ("Baby Blue Sedan," it should be noted, only appeared on vinyl copies of The Lonesome Crowded West). This type of compilation was commonplace in the '60s, when bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and The Who would often release massively successful singles that never ended up on studio albums, but it became increasingly rare as long-playing albums overtook 7" singles as the best-selling format and bands (and/or their labels) started stockpiling their catchiest compositions, rather than rushing them out as quickly as possible. In the modern era, non-greatest hits comps usually just round up B-sides and outtakes.

Before Modest Mouse signed with a major (Epic Records) for The Moon & Antarctica, they bounced around local indie labels, which allowed them the freedom to spew out singles, EPs, and splits without the constraints of big contracts that demand exclusivity. Up Records released their first two albums, an EP, one non-album single, and Building Nothing Out of Something itself, but the comp also includes material from singles the band dropped on fellow Seattle labels Sub Pop and Suicide Squeeze. I have no window into the legal machinations that allowed for this, but it seems like the product of a tight-knit indie scene that lacked the territorial mentality of most majors.

The eclectic array of labels represented on Building Nothing Out of Something is surprising from a logistical standpoint, but far more shocking is how well all of this material hangs together as a full-length. Modest Mouse's first two albums interspersed punk furor, ramshackle indie charm, Americana DNA, and an emo-adjacent, forlorn vibe from song-to-song. This comp, as its title suggests, decidedly favors the last of those identities.

There's one clear outlier, and I'll start with that. I don't just think "All Night Diner" is a bad song that presages the queasy skronkiness of Modest Mouse's post-2000 output—I think it's the one garish wart that prevents Building Nothing Out of Something from being a perfect album. Everything else is either depressing, heartfelt, or philosophical; "All Night Diner" is unsettlingly jittery and horny.

I connected with Building Nothing Out of Something when I was 19, in a particularly sad-sack phase just before I randomly stumbled upon the love of my life. Not at all coincidentally, Fall 2010 was also when I got heavy into American Football, The Glow Pt. 2, and on the more spiteful side, the newly released My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. All of these, save for Kanye's toxic 33-year-old missive, are overly dramatic, moody albums made by men in their early-to-mid-20s. To a 34-year-old, they all sound cringey to varying degrees, but the catharsis and comfort they offered at the time still resonate with me, for better or worse.

In his career, Modest Mouse singer/guitarist Isaac Brock has crafted a few opening riffs with the potential to devastate you before the song really even starts. The intros of "Dramamine" and "Cowboy Dan" convey sparse lonesomeness with their echoey tones and minor keys, but nothing else puts me in this space as quickly as "Broke." Brock's guitar sighs in way that conveys exasperation as much as it does boredom, youthful melancholy as much as it does doomed hopelessness. If "Whenever I Breathe Out, You Breathe In (Positive/Negative)" nails depression lyrically, "Broke" nails it melodically.

The one aspect of the otherwise cohesive Building Nothing Out of Something that outs it as a collection of random material is its varied subject matter. Modest Mouse's first three studio albums all have clear, unique motivations that build on each other: This Is a Long Drive for Someone with Nothing to Think About reflects on touring on a shoestring budget; The Lonesome Crowded West is a treatise on capitalism on the frontier; The Moon & Antarctica is a philosophical musing on purpose and fate. Although sadness is the clear connective tissue of Building Nothing Out of Something, its songs address it from disparate angles.

Brock feels old and alone on opener "Never Ending Math Equation." He's exhausted and numb from driving on "Interstate 8" and "A Life of Arctic Sounds." He's wistfully nostalgic on "Baby Blue Sedan" and "Sleep Walkin.'" He's searching for the root cause of his woes on "Medication" and "Whenever I Breathe Out, You Breathe In (Positive/Negative)." He's outright giving up on "Broke," "Workin' On Leavin' The Livin,'" and "Other People's Lives."

I think each one of Modest Mouse's first three studio albums is a stronger, more focused statement than Building Nothing Out of Something. The comp, however, is more versatile in its ability to address any tangentially blue feeling that rises up in me. If I'm romanticizing the past, "Sleep Walkin'" gets me; if I'm feeling inadequate, "Other People's Lives" speaks to me; if I'm self-destructive, so is "Workin' On Leavin' The Livin;'" if I'm so despondent that it starts to affect my daily interactions, I'm leaning on "Whenever I Breathe Out, You Breathe In (Positive/Negative)."

I've called Modest Mouse my favorite band more than I have any other in my adult life. They also occupy a strange position in my writing career. In 2014, soon after I started a full-time job at a hip hop site, I pitched a bitchy essay entitled "My Favorite Band Has Sucked for a Decade" to an editor at Vice. He accepted it, and this being my first time successfully landing work at a respected publication, I was stoked. I sent him a draft and got no response. It probably sucked, and I have no interest in trying to find it now, but that hurt.

Three years later, soon after I had (ironically) started regularly freelancing for Vice, I pitched a 20th anniversary essay on The Lonesome Crowded West to Stereogum, a site I had admired for years. They published it, and while I'd make some substantial changes if I rewrote it today, I'm still pretty proud of it.

When COVID hit, I was at the peak of my writing career. I was pitching multiple pieces a week to five different websites, and making more money writing than I was from bartending three days a week. The pandemic caused so many layoffs and budget cutbacks that I experienced my first real drought from April to September 2020. With extra time on my hands, I decided to expand my Lonesome Crowded West essay into a full book proposal for the 33 & 1/3rd series, which took about a month-and-a-half. I sent it, and got no response.

~~

To everyone that has ever financially supported Inbox Infinity, and all of the artists and PR people that have granted me access: I can't thank you enough, and I'm sorry that I haven't kept up with my initial mission. From now on, this newsletter will be completely free with no paid tier. I feel guilty getting monthly payments when I publish so infrequently.

I'm still going to write on occasion. It currently feels like pulling teeth, but even in the throes of my bleakest spirals, I try to remember that I'm talented enough to have racked up a fairly impressive resumé. Instead of spreading myself thin to stay on top of every prevailing trend, I'll try to focus on what naturally compels me.

I'm so thankful that I was able to scrape out something resembling a living from my passion for a decade, and I'm sure I'll eventually find something else that I'm good at. If it seems dramatic for me to publicly slam this door shut, just know that the notion has been brewing for a long time, and that writing about it feels like the definitive closure that I've been avoiding. In these last couple years of mostly fruitless listening and pitching, after my previous successes, it's seemed like I'm building nothing out of something.

Giving up on a once-viable career in my mid-30s is scary, especially because so much of my identity, passion, and confidence is wrapped up in this work. Thankfully, like most other bummers I've faced in my adult life, there's a Building Nothing Out of Something lyric that clears my confused fog and succinctly unearths the root of my internal struggles:

Where do you move when what you're moving from / Is yourself?